student responses

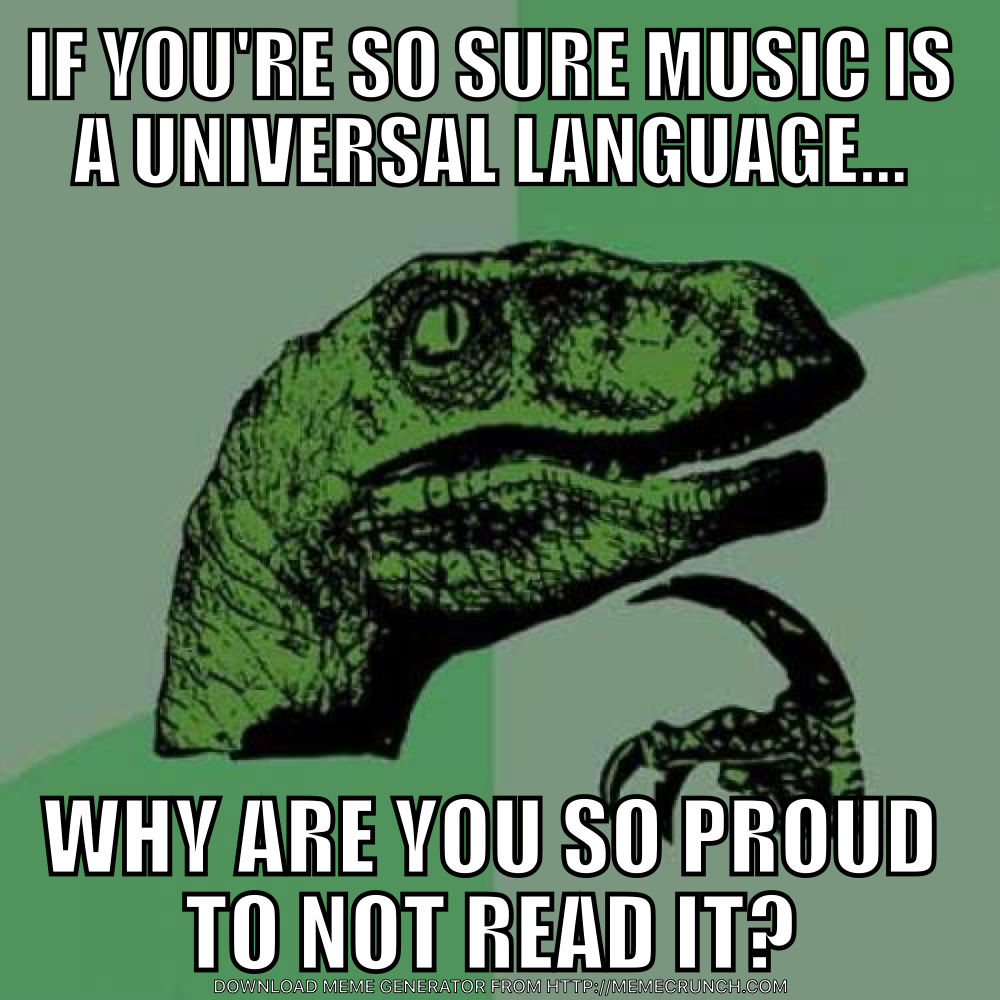

hey all,there's a great deal of turmoil in the news presently--the grease fire that is the 2016 us presidential election, heartbreaking shootings of police in dallas and baton rouge, spiritbreaking shootings of civilians by police in minnesota and louisiana (the former pulled over for having a 'wide nose,' and the latter for selling cd's. no really.), whatever disasters are looming in russia and north korea, et al. this here website is not a powerful engine for social change, and there's a real chance i'm pissing into the wind with posts like this, but very near the top of a very short list of personal beliefs is that music is a powerful aide for many kinds of thought and emotion, and that therefore playing, thinking about, talking about and writing about it is valuable, even in times of strife. but then, everyone wants to think their job is important, and of course on a large enough or small enough time scale, none of them are.that said, teaching music is a wonderful opportunity to hone ones own skills, knowledge, and opinions, and doing so brought me to what became the following piece. i wrote it not too long ago, and offer it as a curiosity, for you to do with as you wish.i hope you and yours are well.colin  i recently taught a course at the university here, and the midterm concluded up a whirlwind summary of classical music with a short essay question:Can intellectual music like Messiaen or Webern be popular? Why or why not?these are the two pieces i played:Messiaen- quartet for the end of time movement 1Webern- variations op 27the students are college-aged, with mixed musical upbringings, and below are the unedited responses i received, reprinted with their permission:1) I believe it could be depending on the listeners. If the music or sounds associate to certain more enjoyable memories, then the music is more of a passage way into their mind aside from them actually listening to the music. Their shift of focus would then be on what the music reminds them of with the music as a background piece.2) It can be popular depending on when or how people listen to it. It wouldn’t be considered main stream “popular” because people do not want to “think” about music let alone instrumental music. It can be popular amungst [sic] certain types of people but not a world-wide popularity. I think it was more of a cultural appriciation [sic] than popular.3) No intellectual music cannot be popular because the average person who listens to popular music is not intellectual. If intellectual music is popular it must definitely resemble popular music in one way or another.4) It can be, but most people would agree that it is, and could not, be popular. The sounds are too harsh and it is too similar to the sound of someone going crazy. There is no discernible melody and nothing that is desired to be pleasurable. Most people, when listening to music, want something specific; an upbeat, sad, or singable song. Messiaen and Webern do not fit into this qualification.5) Yes, because all music is abstract, all music has a niche somewhere in the world. Intellectual music can be used for a vast number of purposes even if one or many people dislike it. Even if the piece of music is despised outright by everyone, it would still have been a popular piece.in teaching this and other thornier music, we spoke of different ways to listen—the idea that an expectation of melody, regular pulse, repeating harmony, etc, was only one possible way to hear. further, each piece was placed in an historical context, an emotional or intellectual context, and a physical context where it would have been performed. last was to describe how certain notes or rhythms were derived: symmetrical and gestural constructions in the Webern; passages from the book of Revelations, and isorhythms with prime numbers in the Messiaen, etc. we discussed nature versus nurture in terms of dissonance/consonance and the fallacy of major=happy minor=sad; whether a 100% abstract thing like sound can be useful to the mind as well as the ‘soul’; and the idea of using sound to check in to your own brain and the world around you, rather than check out.in good news and as a slight rebuttal to the tone of answer 4, there is fresh science out which reinforces the notion that our seemingly inherent preference for consonant intervals is only that: seemingly inherent, and nothing more. a tribe in the Amazon with minimal exposure to western music correctly identified emotions in voices, but showed no preference whatever for consonant or dissonant intervals.in bad news which lines up rather well to answers 2 and 3, there is fresh science out showing a slight evolutionary bias against education, even though the internet has rendered that bias null for the time being.in a fantastic lecture in antwerp, the artist Lawrence Weiner tangentially addresses this, saying that we’ve effectively been dancing to “Melancholy Baby” for 50 years, and that that should worry us. i have heard and read very serious and high level musicians argue that a pentatonic scale is in our very DNA, and we now know that to not be true—the musical enculturation is so great and so complete that we generally don’t realize it’s happened, and we see purveyors of alternate harmonies as outliers not just for their choice of sounds, but often also see their lifestyles as engendering their bizarre sounds. (to wit, years ago i played a church service at the request of a friend, which we concluded with a Monk tune—i don’t remember which one, but it could have been ‘Straight, No Chaser’. the priest began his sermon by saying he liked Monk’s music because it reminded him that we’re all broken. fuck you, buddy.) it is possible to play a major third so aggressively that you come off as a crazy person, and likewise possible to play a minor ninth with great tenderness, to say nothing of the palate of non-equal tempered harmonies.i know some of you who are here are musicians, and of those some of you find Messiaen and Webern downright singable, so i’m offering these responses as a reminder of the listening habits of an average audience, ‘civilians’ as my friend Jim calls them, that we may bear them in mind when performing or speaking about more adventurous material. at a lecture he gave at a conservatory in new york while i was going there, the great contemporary percussionist Steve Schick bemoaned his upcoming performance conducting Beethoven 4 by saying “when you spend years memorizing 'Ionization' and 'Bone Alphabet,' Beethoven just gets stuck in your head.”if you found the two first examples difficult but are curious to dig a bit deeper: try to notice why you dislike it, and if the answer is any variation on ‘it’s unfamiliar,’ please listen to it two or three times in a row (as Stravinsky did in his later premieres), and see what happens. i’d love your thoughts on the music and the responses.frankly some of the answers made my head and heart hurt. in discussing them, a dear friend summarized one of them thusly: “if you make a sound and someone likes it, then you are dumb for making it, and they are dumb for liking it.”remember: pop music=mcdonalds. …happy musicking everyone.

i recently taught a course at the university here, and the midterm concluded up a whirlwind summary of classical music with a short essay question:Can intellectual music like Messiaen or Webern be popular? Why or why not?these are the two pieces i played:Messiaen- quartet for the end of time movement 1Webern- variations op 27the students are college-aged, with mixed musical upbringings, and below are the unedited responses i received, reprinted with their permission:1) I believe it could be depending on the listeners. If the music or sounds associate to certain more enjoyable memories, then the music is more of a passage way into their mind aside from them actually listening to the music. Their shift of focus would then be on what the music reminds them of with the music as a background piece.2) It can be popular depending on when or how people listen to it. It wouldn’t be considered main stream “popular” because people do not want to “think” about music let alone instrumental music. It can be popular amungst [sic] certain types of people but not a world-wide popularity. I think it was more of a cultural appriciation [sic] than popular.3) No intellectual music cannot be popular because the average person who listens to popular music is not intellectual. If intellectual music is popular it must definitely resemble popular music in one way or another.4) It can be, but most people would agree that it is, and could not, be popular. The sounds are too harsh and it is too similar to the sound of someone going crazy. There is no discernible melody and nothing that is desired to be pleasurable. Most people, when listening to music, want something specific; an upbeat, sad, or singable song. Messiaen and Webern do not fit into this qualification.5) Yes, because all music is abstract, all music has a niche somewhere in the world. Intellectual music can be used for a vast number of purposes even if one or many people dislike it. Even if the piece of music is despised outright by everyone, it would still have been a popular piece.in teaching this and other thornier music, we spoke of different ways to listen—the idea that an expectation of melody, regular pulse, repeating harmony, etc, was only one possible way to hear. further, each piece was placed in an historical context, an emotional or intellectual context, and a physical context where it would have been performed. last was to describe how certain notes or rhythms were derived: symmetrical and gestural constructions in the Webern; passages from the book of Revelations, and isorhythms with prime numbers in the Messiaen, etc. we discussed nature versus nurture in terms of dissonance/consonance and the fallacy of major=happy minor=sad; whether a 100% abstract thing like sound can be useful to the mind as well as the ‘soul’; and the idea of using sound to check in to your own brain and the world around you, rather than check out.in good news and as a slight rebuttal to the tone of answer 4, there is fresh science out which reinforces the notion that our seemingly inherent preference for consonant intervals is only that: seemingly inherent, and nothing more. a tribe in the Amazon with minimal exposure to western music correctly identified emotions in voices, but showed no preference whatever for consonant or dissonant intervals.in bad news which lines up rather well to answers 2 and 3, there is fresh science out showing a slight evolutionary bias against education, even though the internet has rendered that bias null for the time being.in a fantastic lecture in antwerp, the artist Lawrence Weiner tangentially addresses this, saying that we’ve effectively been dancing to “Melancholy Baby” for 50 years, and that that should worry us. i have heard and read very serious and high level musicians argue that a pentatonic scale is in our very DNA, and we now know that to not be true—the musical enculturation is so great and so complete that we generally don’t realize it’s happened, and we see purveyors of alternate harmonies as outliers not just for their choice of sounds, but often also see their lifestyles as engendering their bizarre sounds. (to wit, years ago i played a church service at the request of a friend, which we concluded with a Monk tune—i don’t remember which one, but it could have been ‘Straight, No Chaser’. the priest began his sermon by saying he liked Monk’s music because it reminded him that we’re all broken. fuck you, buddy.) it is possible to play a major third so aggressively that you come off as a crazy person, and likewise possible to play a minor ninth with great tenderness, to say nothing of the palate of non-equal tempered harmonies.i know some of you who are here are musicians, and of those some of you find Messiaen and Webern downright singable, so i’m offering these responses as a reminder of the listening habits of an average audience, ‘civilians’ as my friend Jim calls them, that we may bear them in mind when performing or speaking about more adventurous material. at a lecture he gave at a conservatory in new york while i was going there, the great contemporary percussionist Steve Schick bemoaned his upcoming performance conducting Beethoven 4 by saying “when you spend years memorizing 'Ionization' and 'Bone Alphabet,' Beethoven just gets stuck in your head.”if you found the two first examples difficult but are curious to dig a bit deeper: try to notice why you dislike it, and if the answer is any variation on ‘it’s unfamiliar,’ please listen to it two or three times in a row (as Stravinsky did in his later premieres), and see what happens. i’d love your thoughts on the music and the responses.frankly some of the answers made my head and heart hurt. in discussing them, a dear friend summarized one of them thusly: “if you make a sound and someone likes it, then you are dumb for making it, and they are dumb for liking it.”remember: pop music=mcdonalds. …happy musicking everyone.